Krutch Park (pronounced krootch) is a suffocated little one-acre green space smack in the middle of downtown. Funded by and named after Charles Krutch, who photographed TVA’s massive growth in the middle of the 20th century, it has three picnic tables, a pond you can jump across, and a parking lot you aren’t allowed to park in. According to the sidewalk sign, it was founded as a “quiet retreat for the pleasure and health of the public.” This park also has sculptures, which we are here to give awards to. But first, a word about Charles Krutch and the park itself.

Krutch’s photographs were some of the first identified as “fine art” in the field of photography, and a quick survey of his TVA dam pictures proves why:

Obviously, this type of photograph does much more than document. It captures, with dramatic urgency, the contrast of tiny humans swallowed in the enormity of these energy machines. You’ll miss the Waldo staff members unless you squint.

He’d only been photographing for TVA three years when his work started to be featured nationally in the New York Times. He continued working for TVA until his death in 1981, when he bequeathed the money for his namesake park.

It’s against the backdrop of his work for TVA–his photography’s sublime, sensitive treatment of lifeless, pragmatic superstructures–that we consider the art in Krutch Park. Because the art in Krutch Park is faced with the same challenge Krutch himself faced: how to elicit “A quiet retreat for pleasure” in the midst of concrete walls and corporate logos. The park itself hardly accomplishes this. It’s too small. To sit down on one of its benches produces the feeling of waiting in a very cost-sensible atrium of a corporate high-rise. There are no doubt thirty backyards in Sequoyah Hills that outshine it.

I’m sorry Charles. I’m sure the city did their best with what they had.

But what about the art? As far as my research determined, sculptures weren’t part of Krutch’s original will for his park. What can they do for the congested home they find themselves in? Well, that’s the beauty of sculptures like these. At their best, they transform the space into something vitally non-functional. A wonderful kind of non-functional. The claustrophobic half-block opens up into something spacious. Something purely for pleasure. Something worth paying attention to and recognizing.

Five awards. We’ll start with three superlatives and end with our runner-up and best in show.

Most Likely to End Up at Dollywood:

At Home with Higher Thoughts, Charlie Brouwer

As it is, this is too subtle and mystifying for a theme park. So, some ideas for Dolly: Put a pair of silly eyes on this. Hollow out the back for a speaker playing fiddle tunes. Mark the legs with a “yer mountain bumpkin must be yea-tall to ride” measuring line. Punch a hole in the front so an animatronic bird can pop out and whistle Rocky Top.

Worst Bargain

White Stardust, Elizabeth Akamatsu

Did you know that the sculptures in Krutch Park are up for sale? They are. And you can buy White Stardust for fifty thousand dollars. It is, by far, the most expensive piece in the park. The problem is, its also the worst piece. It would have been okay, but somebody decided to emblazon “We are stardust” on its base plate. An interesting sculpture toying with perspective and two-dimensional planes saddled with an Instagram caption. For the price of a Cadillac.

Hardest Not to Climb On:

Space Diamond, Coral Lambert

Possibly the highest praise I can lavish on an abstract sculptural piece is “I want to play on it.” Part of what makes playground architecture so compelling is the sense of absurdity and pointlessness, and sculpture can succeed by the same metric. We find ourselves wanting to climb and traverse. Space Diamond employs rough, construction-ready materials in a playful geometric tent, and looks like an alien cage asking to be explored.

Best in Show Runner-Up:

Ecstatic Crepitacean, Will Vannerson

Here, pipes shine and join like we’ve seen them before in car exhausts and dryer ducts and air conditioning systems. But Vannerson twists them into an organic network, mirroring veins or roots or elbows. The result is neither retro-futuristic or fantasy, but other-worldy nonetheless, provoking comparisons between the organic and the synthetic or the efficient with the beautiful.

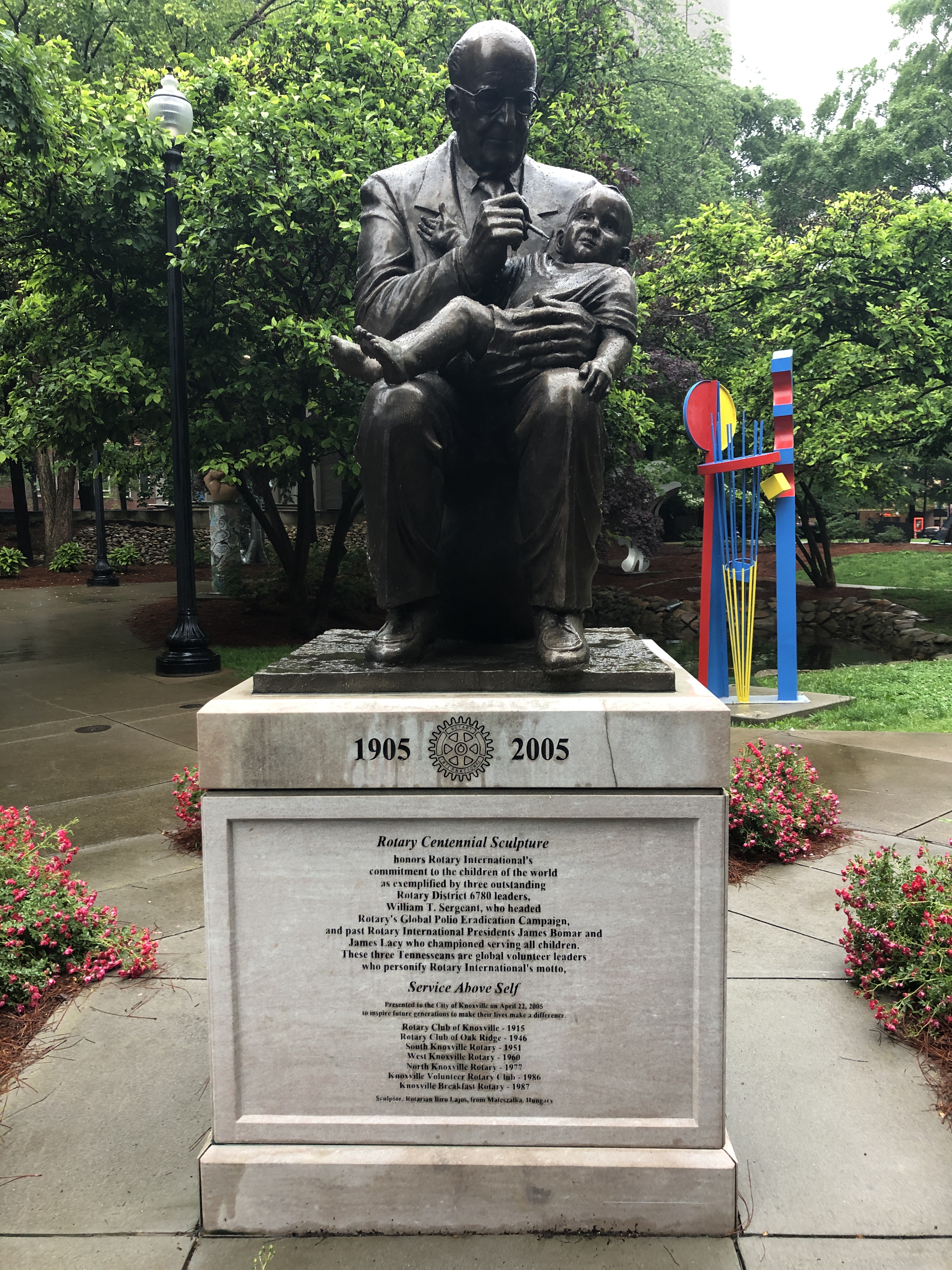

Best in Show:

Motion Light, Hanna Jubran

Motion Light is the very sort of sculpture that makes you glad to walk through Krutch Park. It is all of the things I’ve praised above: playful, alien, and thought-provoking. It manipulates the simplest formal conceits–straight lines, primary colors, circles and squares–to create something invitational and childlike without sacrificing sophistication. I don’t think there is any secret meaning here to be puzzled out. Like the other sculptures in Krutch Park, it is meant to be lived beside and strolled past, somehow enlivening those in its proximity. Like Charles Krutch’s photographs, dramatic contrasts (color from color, straight line from curve, etc.) underline what may well blend into the rest of the environment as furniture.

You can find the rest of the sculptures below. If you have a favorite, maybe we can nominate a Balltower Reader’s Choice Award.

Thanks for stopping in.

Michael

I think Krutch Park functions a lot better as a transitory space than it does a place for rest–besides being, as you said, too small, it’s too heavily trafficked with pedestrians to be much of a place to just sit down and contemplate your surroundings. But I love walking through the park, and it’s a great change of visual pace from the blocks surrounding it.

As for Readers’ Choice, I like the one near the bottom-right that looks like silver pulled taffy. Not sure of the title of the piece, but I dig it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Okay! One vote for Jacob Burmood’s aptly named “Crumple and Flow.”

LikeLike